Days at the races

As a teenager I use to go up to Romford dog track on Friday nights for a bit of a drink and a punt.

If you could be bothered to wander track-side there were on-course bookies, but as mug punters we normally stayed in the bar & bet on what was known as ‘the Tote’ – essentially a pool of all bets from which payouts were made to the lucky few winners.

The fixed odds changed according to how much money was bet on each greyhound, with the Tote routinely creaming off a 20% grab (nice work if you can get it!).

Smash & grab

Most of us just had a few beers & a bet on our favourite name or number dog (I liked 1 and 2 on the inside traps, the ‘railers’), though some hardcore punters would spend hours studying the form before making a bet.

In theory the die-hards should’ve made good money given that so many bets were placed randomly, but since the odds automatically shifted to reflect larger bets & because the Tote took such a big grab, it was still hard to make money from this pari-mutuel system.

There are some parallels with the stock market here: just buying today’s most robust companies doesn’t necessarily work, partly because things don’t always play out as expected, and partly because the market recognises which companies are strongest & prices them accordingly.

You can then get very quickly lost in a maze of probability calculations.

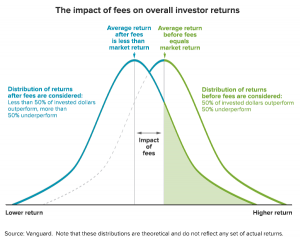

The impact of fees

Most equity fund managers are fearful of diverging too far from the annual return of the index, so they tend to hold a sizeable portfolio of stocks instead of having confidence in a few great ideas.

The problem is that after accounting for their fund management fees, performance fees, transaction costs, slippage, market impact, and taxes, the average return from a fund is likely to be worse than the market return.

You’d do better with a low-cost index fund.

Some high-profile fund managers seem to spend an extraordinary amount of time on media & marketing, but are less successful at delivering returns for investors (statistically some have to beat the market some of the time; but on average the returns aren’t very good over time).

How you can get ahead financially

Charlie Munger explained in a brilliant Berkshire Hathaway article, The Art of Stock Picking, how a small handful of experts can and do beat average market returns, and here’s what they had in common:

- they very seldom bet;

- when they have the odds in their favour they bet big; and

- they invest for the long term, so they don’t pay much tax

The problem facing so many fund managers is that by striving to beat the market marginally in any given financial year they holds dozens of positions and trade way too often, which in aggregate achieves nothing.

As Munger explains so clearly, if you buy a quality investment and allow it to compound for 30 years, before paying one chunk of tax at the end – the difference this makes to your returns compared to buying & selling investments annually is so large as to be astronomical.

Alas in this digital age you’d have more success trying to convince people to bet on the ‘railers’ than make sensible long-term investments.