From shortage to surplus

A true story.

I might’ve previously mentioned in my predilection for Guinness as a youth and young man.

Once a year, me, my many brothers (Catholic family), my then business partner Paddy Allen, and a range of related associates used to get back together for Xmas and head off to our favourite pub, where we’d all previously worked as teenagers.

Inevitably the meagre stock of Guinness kegs would be drunk dry within a few convivial hours.

Each year the landlord, Fred (who was fairly fond of a tipple himself), could hardly believe his luck at the unexpected spike in Guinness sales, and would then go about ordering a huge stash of kegs in anticipation of the next big windfall.

Unfortunately, since adulthood we’d flown the nest we all lived and worked miles away, so the truckload of Guinness kegs would sit in the basement more or less untouched for 12 months until the next annual Christmas bash.

Cracking the whip

A small movement of a hand cracking a whip can lead to a violent movement at the end of the whip, and a dramatic cracking sound.

The bullwhip effect is a supply chain phenomenon, whereby relatively small fluctuations in consumer demand can lead to much larger fluctuations in demand further down the chain.

When a retailer sells more product – a bit like our vivacious landlord, Fred, for example – it’s often assumed that customers will start buying more of the same product, leading to their increasing of orders from the distributor.

The distributor then orders more from the manufacturer – plus a bit extra to be on the safe side – and then the manufacturer produces an ever larger quantity of the product, partly because it’s often cheaper to produce in bulk.

A small change in demand may be amplified up by the supply chain, meaning that relatively small errors in forecast demand can lead to significant gluts (or shortages) down the track.

While a glut may not be followed by a shortage, it almost always seems to be the case that a shortage is followed in time by a glut.

From shortages to gluts

Even when consumer demand is relatively stable, we may find that a small change in the real of predicted demand for a product can result in a larger increase in wholesale orders by manufacturers, leading to supply and demand tilting out of balance.

Now in 2022 there was a global shortage of semi-conductors, for example, as demand reawakened before supply could adequately respond.

In Australia and New Zealand there were chronic shortages of building materials, sending prices skyward.

In 2023 things will begin to swing the other way, and we’ll begin to see global gluts in all manner of goods and commodities, ranging across anything from computer chips and laptops, to shipping containers, natural gas, and oil, to red wine, hogs, pink salmon, sugar, milk powder…well, pretty much everything basically.

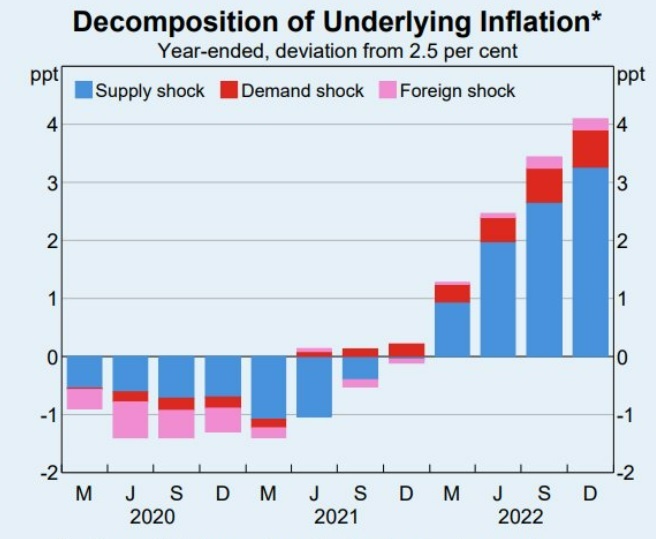

The world economy reopens: unprecedented supply shocks

Australia effectively closed its international borders for a couple of years through the pandemic, and carried out some of the world’s longest lockdowns – unprecedented moves leading to painful labour shortages, with a burst of consumer price inflation in 2022 mostly resulting from the supply chain disruption.

The good news is that supply chains are recovering quickly, and with the borders now open population growth into Australia is running at a record high of around ½ million per annum.

As sure as night follows day, just as everyone was taken aback and scratching their heads about the surge in global inflation in 2022, soon enough they’ll be perplexed as goods and commodity prices start plunging in the face of epic supply gluts.

Cups to runneth over

People can move location very quickly these days once visas are processed, so the labour shortages of 2022 will soon be replaced by the labour force growing far more quickly than jobs can be created and filled, and unemployment will begin to rise back towards 5 per cent.

Australia is currently experiencing a chronic shortage of housing, but although it doesn’t feel likely at the moment, one day in the future we’ll have another glut of high-rise units, since that’s the way the cycles work.

Building approvals are currently running at the lowest level in 2 years though and falling, though.

And since it takes 2 to 3 years on average to deliver medium-density stock the next surge in dwelling completions likely won’t be seen until 2026 at the very earliest.