Learning from failure

In his excellent book Black Box Thinking, Matthew Syed examined how individuals and businesses can learn from failure, through marginal gains, rigorous testing of what’s working & what isn’t, and adjusting course appropriately.

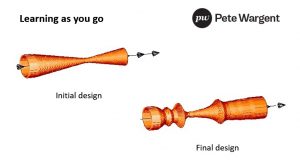

He cites the fascinating (to me, anyway!) case of Unilever’s laundry detergent nozzles, which continually became blocked, baffling crack mathematicians & engineers alike, while costing the group dearly in revenues foregone.

The solution was discovered through the testing 10 nozzles of various lengths, then creating 10 copies of the most effective design with slight modifications, and repeating this iterative process through nearly 450 prototypes until a solution was found, effectively through trial & error.

The interesting thing to me was how the final design was totally different to anything that could have been envisaged by scientists, maths geeks, or engineers.

No master plan; no preconceptions about how the final model should look. It just…worked.

Minimum viable product (MVP)

One of the challenges facing startup businesses & entrepreneurs is that they can spend weeks, months, or even years developing & fine-tuning a product before launching it, only to discover that a competitor has captured the bulk of the market or the environment has changed.

This is where the concept of the minimum viable product or ‘MVP’ (Ries, 2011) comes into its own, forcing startups to get out into the market as soon as practicable, listening to the market’s response, then learning to adapt, pivot, or respond accordingly.

The final product or design may not be much like what you had in mind at the outset, but no matter, for you will have discovered what there is a genuine market for, how much your target customers are prepared to pay for it, & how to tweak the service offering until it’s profitable.

Low initial overheads can help.

Good & bad failures

There’s arguably something in this concept for investors, too, for markets & economies are forever developing, and investing strategies evolve accordingly.

There’s a strong reasoning in favour of taking action & getting started instead of procrastinating or trying to find that elusive ‘perfect investment’.

If you want to learn any skill, what’s important is what happens after a failure, and how you respond to it.

In saying that, events over the past fortnight have illuminated the potentially disastrous impacts of taking poor or conflicted advice and undue risks.

Failure is a natural part of learning, but when people fail dramatically they often give up, and so learn little.

—

Markets are fickle & unpredictable, so it may be helpful to develop an investment hypothesis and criteria for success that aren’t solely connected to weekly or monthly market prices.

In other words, risk management, due diligence, & the process are critical, as well as the immediate results.